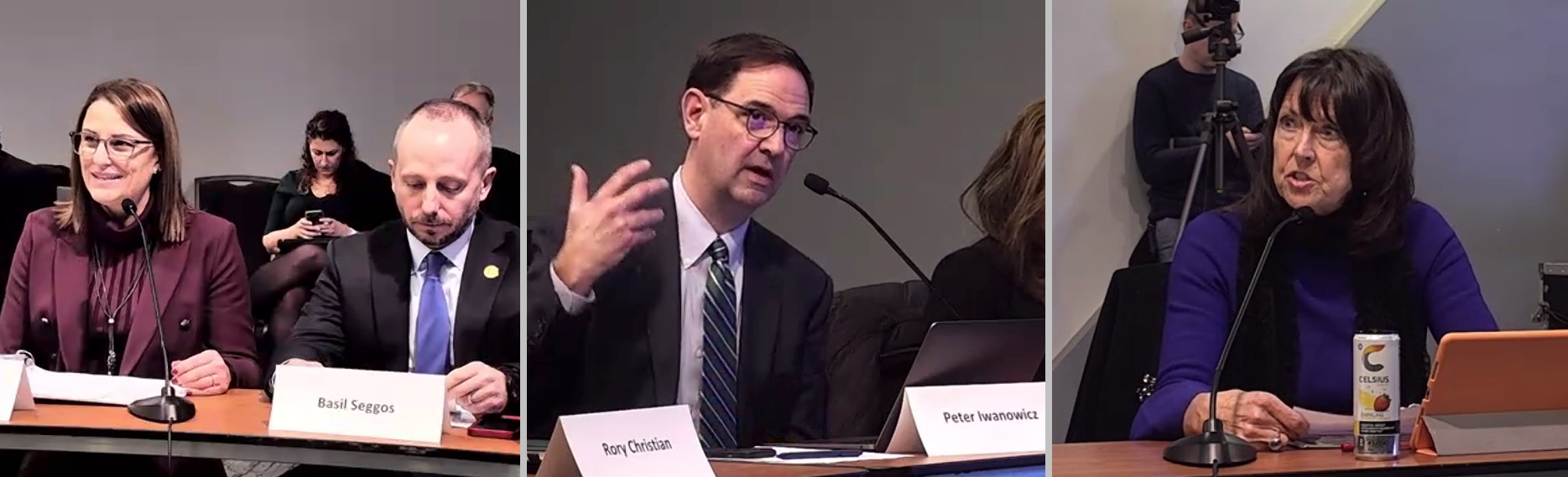

New York Finally Has a Climate Plan. Now Comes the Hard Part.

More than three years after the state passed its sweeping climate bill, the ball is back in lawmakers’ court.

Low-wage manual laborers can sue to make their bosses pay them weekly. Hochul’s late-breaking budget addition may undermine that right.

New York’s transparency watchdog found that the ethics commission violated open records law by redacting its own recusal forms.

New York has one of the weakest consumer protection laws in the country. This year’s state budget may change that.

The Assembly and Senate want to beef up labor standards and farmland protections for clean energy projects. Developers say that would slow down the energy transition.

State investigators accused the gas utility of “sloppiness” in managing customer funds, but took a light touch in enforcement.

What are industrial development agencies?