Crucial Evidence Goes Stale As Desk Appearance Tickets Are Issued For More Serious Crimes, Leaving Defendants In Purgatory

Defendants given desk appearance tickets may not be assigned a public defender until 20 days after their arrest. That means crucial evidence in cases involving possible jail time could go missing.

Previously unreleased disciplinary files expose officers who beat, slap, and pepper spray the residents they’re supposed to protect. Most are back at work within a month.

Local regulations haven’t kept up with the rollout of new surveillance tech. Some reformers see Washington as their best hope.

Stark disparities in access to life-saving medication for opioid addiction persist between facilities — and racial groups.

Referencing a New York Focus story, Assemblymember Jessica González-Rojas introduced legislation to prevent public agencies from naming the medically discredited condition in their reports.

In the New York City teachers union, anger over a plan to privatize retiree health care could send a longshot campaign over the edge.

Migrants from Mauritania and Senegal were the most likely to receive eviction notices, but not the most populous groups in shelters, a New York Focus analysis found.

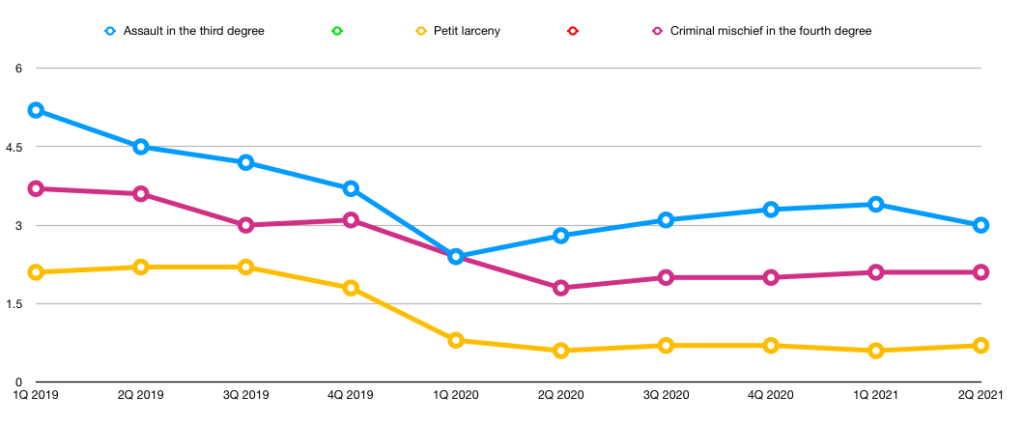

Rate of custodial arrests as compared to DATs for three leading DAT eligible offenses. Source: NYPD

Rate of custodial arrests as compared to DATs for three leading DAT eligible offenses. Source: NYPD